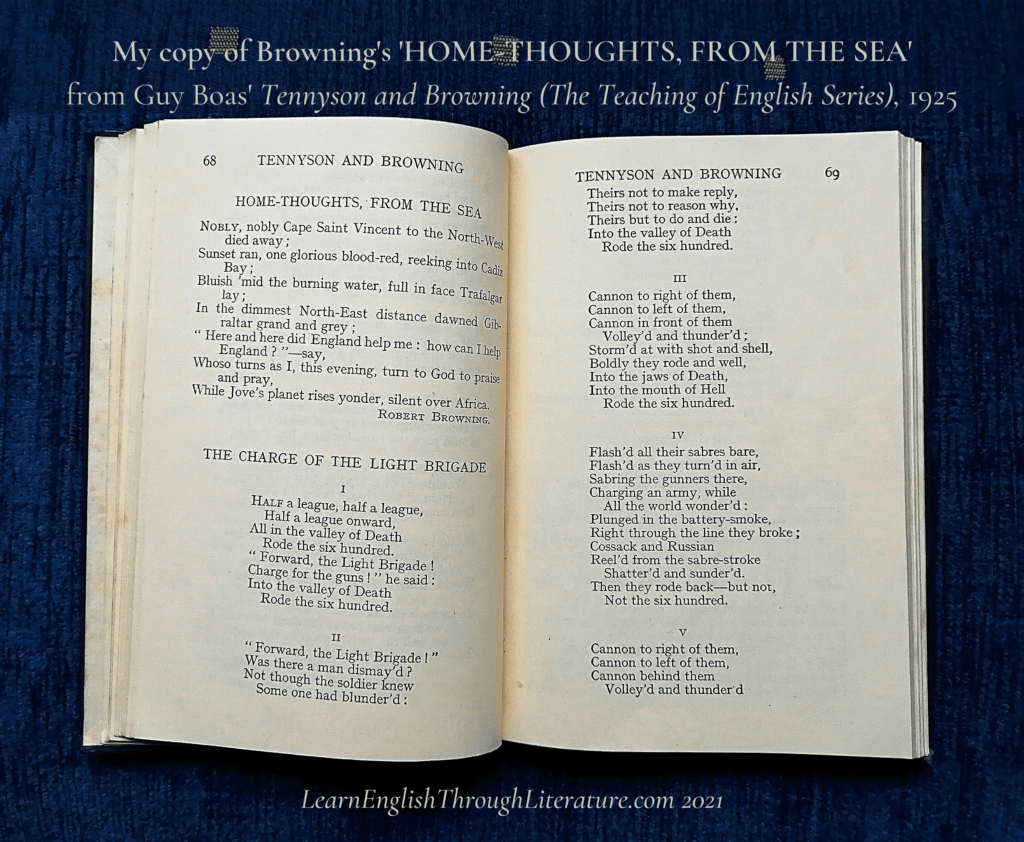

📜 ‘Home-Thoughts, From the Sea’ (1845)

Nobly, nobly Cape Saint Vincent to the North-West died away;

Sunset ran, one glorious blood-red, reeking into Cadiz Bay;

Bluish ‘mid the burning water, full in face Trafalgar lay;

In the dimmest North-East distance, dawned Gibraltar grand and gray;

“Here and here did England help me: how can I help England?”—say,

Whoso turns as I, this evening, turn to God to praise and pray,

While Jove’s planet rises yonder, silent over Africa.

– Robert Browning

…

Have you ever travelled far from home? More specifically, have you ever had the experience of spending a night aboard a ship? 🛳️

This poem, as its title suggests, is about an Englishman’s experience of travelling far from home.

On the one hand, it describes the novelties (new aspects or qualities) of any travelling adventure, and on the other hand, it is detailed and specific to the geographical location the poet, Robert Browning, is in (sailing between Spain, Portugal, and the North African coast) and the historical age he is living in (the middle of the nineteenth century – 1840s).

📝 APPRECIATION AND ANALYSIS OF THE POEM

When I first read this poem, it brought to mind the shifting (constantly moving) currents of water around him. He was quite literally in the ‘middle of the sea‘ when he was inspired to pen (write down with a pen) these lines. His ship (or boat) seems to be as distant from the Portuguese shore as it is from the African coast. 🌊

The scene is inspiring: a beautiful sunset over the waters, with spectacular mountain ranges in the distance. It is also serene (restful, peaceful), and we can imagine Robert Browning leaning against the ship’s railing, meditating quietly. This internal groundedness contrasts with the instability and movement of the waves about him. ⚓

He reflects on his deep appreciation for and perspectives on these new places, using vivid language such as:

- Nobly, nobly: The fact that Browning repeats this word twice shows just how much he is impressed by the sights he is witnessing at that moment. The Cape of Saint Vincent is the most south-westerly point of Portugal, jutting out (sticking out) into the Atlantic.

✍️ You will notice just how often he reverts (turns to) visually evocative words throughout this poem.

- Sunset ran: Notice how he uses the verb ‘to run’ to describe the sunset’s energy and dynamism.

- one glorious blood-red, reeking into Cadiz Bay: This line describes the sunset’s colours as if they were made of blood, a vital fluid that is ‘reeking‘ (giving off, spilling) into the bay. The word ‘glorious‘ here also evokes (has a quality of something else that reminds us of it) the idea of soldierly victory and glory, as if the sunset were a person who died on a battlefield with full military honours.

- Bluish ‘mid the burning water: Here the colours change from ‘blood-red’ to ‘bluish’. Could it be that he is noticing the reflections of the darkening night sky on the waves, mixed with orange and red reflections from the ‘burning’ sunset?

- full in face Trafalgar lay: This phrase is impressive in its assonance and alliteration, as well as how it uses words with short syllables to give the impression of strength and immutability (the quality of not being able to be moved; fully fixed and established).

This is important here because his reference to Trafalgar is more than just a geographical description: the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) was a decisive British victory against Napoleon to establish their supremacy (being superior) in naval affairs (‘naval’ comes from the word ‘navy’, which is the branch of a state’s army that serves on ships and fights at sea). This battle was therefore deeply symbolic for the British and we sense Browning’s quiet pride as he acknowledges it here.

- In the dimmest North-East distance, dawned Gibraltar grand and gray: Gibraltar, as a strategic British outpost and colony in the area, is also a place of pride. It is described like a dawn, ‘grand and gray‘, in contrast with the ‘dimmest North-East distance‘, that is, other parts of the Spanish and Portuguese coastline.

At this point, his tone changes from one of wonder at the beauty of nature and pride in its British associations to a sudden prayer, as if he has just made an unexpected, abrupt discovery. ✨

His feelings shift (change direction) into an appreciation for the home, England, he has left behind.

“Here and here did England help me: how can I help England?”—say,

Whoso turns as I, this evening, turn to God to praise and pray, …

Notice how he uses the imperative tense here: ‘say’, ‘turn’, etc. All of these indicate (show) that he is turning to the reader and addressing him or her directly. He is urging them to remember that ‘England [did] help’ them once and that for this reason they should never forget to do any service for their country while they are away. (It reminds me of a famous line of John F. Kennedy’s, in which he said “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”.)

Whoso turns as I, this evening, turn to God to praise and pray: The opening word ‘whoso’ here is short for ‘whosoever’ or ‘whoever’. Again, he is addressing the reader openly as a ‘whoever’; he eagerly invites them to ‘turn to God to praise and pray’, just as he himself is now doing on ‘this [unforgettable] evening’.

The poem ends with a line that draws our focus away from his inner thoughts and connects them back with the wonderful world around him, the creation of the same God he has just praised and prayed to.

While Jove’s planet rises yonder, silent over Africa.

‘Jove’s planet’ is another name for Jupiter, which can sometimes be seen as a very bright star in southern skies. Being the largest planet in the solar system that we know of, it impresses readers like us with admiration and reverence (deep respect) for the universe we are a part of within his God-ordained system. ✨

That last phrase, ‘silent over Africa’, works like a closing ‘hush‘, a ‘decrescendo’ (to use a musical term) after all the excitement that has occupied Browning before. The last word, ‘Africa’, is symbolic in itself: it is a vast continent that, even in that time, had hardly been explored by Europeans and was a subject of endless fascination and mystery.

…

📝 CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS

All in all, this poem is an exploration of a traveller’s thoughts. It is full of the poet’s sense of wonder all the way through: wonder at the sunset’s beauty, the marvels of this exotic landscape and its history, and awe towards the God who created such a vast world and universe.

While I have travelled to some beautiful places, I have never put my impressions into such stirring or memorable words as Browning did! That said, we must remember that because overseas travel was so arduous (difficult) in his time, it gave travellers or tourists the opportunity to appreciate everything in finer detail. The allure (strong attraction, draw) of travel was strong for many Britons: the European continent was accessible across the English Channel, while Britain continued to expand its empire further afield. It was customary (common) at the time for artists and young men of affluent means (rich resources) to travel throughout Europe for the purpose of ‘cultivating‘ (develop) their cultural tastes – a rite of passage (an event that marks a new stage or growth in life) called ‘the Grand Tour’.

It is not exactly clear whether or not Browning was on a ‘Grand Tour’ at this time – we know that he did visit northern Italy around this time. But whatever the purpose of his journey, he certainly discovered many enriching moments and captured them eloquently (elegantly and persuasively) in verses we are privileged to enjoy today!