📕 ‘You have moral and literary tastes in common. You have both warm hearts and benevolent feelings; and, Fanny, who that heard him read, and saw you listen to Shakespeare the other night, will think you unfitted as companions?’

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

…

Our lesson today is a ‘Reading Comprehension Lesson’, which is best suited for intermediate to advanced-level students.

I will give some background information about ‘Mansfield Park’.

Then, with the aid of vocabulary and grammatical explanations, we will read a few of Austen’s original sentences. You may use your own vocabulary list from the bolded words and phrases below.

…

BRITISH LITERATURE AND TRADITIONS OF NARRATION 🌹

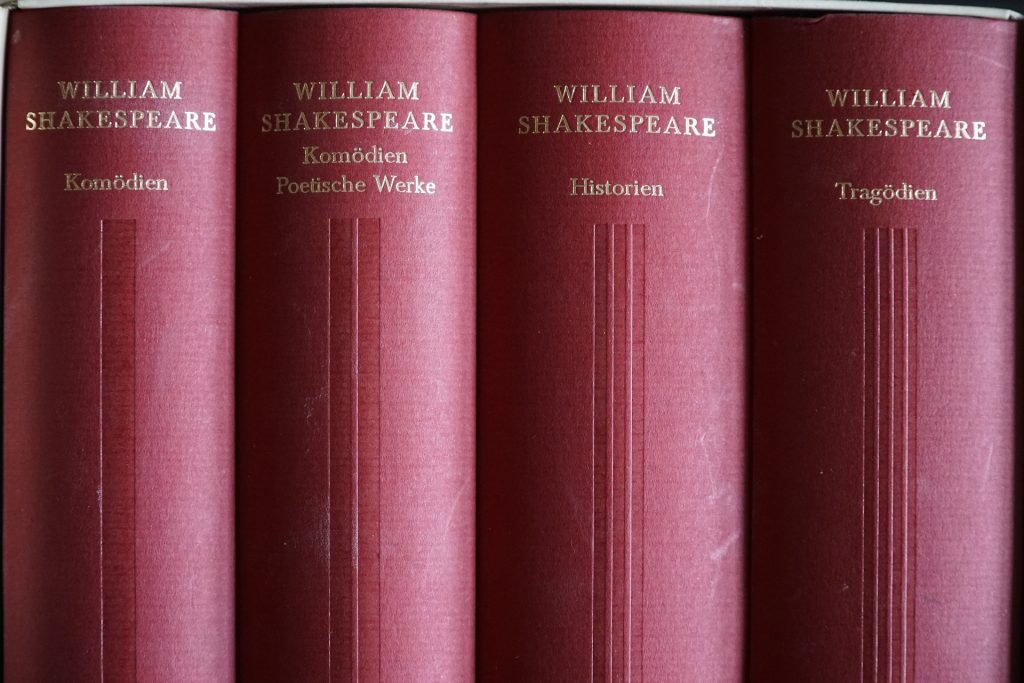

If you’ve ever read one of Jane Austen’s books and found it enjoyable, you’ll definitely recall how she often incorporates casual references to Shakespeare, whether it be in a sentence or a word or name.

In fact, British families frequently read plays, poetry, or even prose (texts like novels that are not poems) aloud at home when Austen was writing her books (in the early 1800s). A simple, shared entertainment that also had educational value!

Thus, many families took pride in the practise of narration, which involves reading and explaining a work aloud. For them, it was crucial that their kids know how to interpret, to feel deeply and think carefully about everything they read.

…

HOW SHAKESPEARE IS AN IMPORTANT PART OF MANSFIELD PARK 🌹

In all of Austen’s novels, Mansfield Park is the one which Shakespeare mostly explored. Scholars agree that no other novel of Austen’s is so full of references to Shakespeare – direct or indirect – as her longest work.

In fact, Mansfield Park uses drama and the theatre as topics (subjects and themes) throughout the story. If you are familiar with the book, you will remember that at one point the young people at Mansfield Park House start planning to perform a play. They spend a good while (a long time) trying to choose which play is best:

📕 ‘All the best plays were run over in vain. Neither Hamlet, nor Macbeth, nor Othello, nor Douglas, nor The Gamester, presented anything that could satisfy even the tragedians …’

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

In many ways, like Shakespeare, Jane Austen was a master at interweaving (linking different parts into a larger work of art) small pictures with bigger ones and connecting individual stories with the larger scenario.

She demonstrates this most well, in my opinion, in two specific circumstances.

🎭 SCENARIO 1: ACTING A HOME PLAY IN MANSFIELD PARK

IIn the first half of the story, the main protagonist (character), Fanny Price, is only one among the many young people in Mansfield Park. She seems to be lost among the boisterous Bertram siblings, Mr. Rushworth, Tom Bertram’s friend John, and the Crawford couple, Mary and Henry, because she is a shy girl.

In a famous scene, Fanny objects to (she disagrees to participate or take part in an action) joining in the acting. She knows that her uncle, Sir Bertram, who is absent (not present, not there), would not be pleased (happy) to find his children acting in a play with strangers.

Sometimes contemporary readers (of modern generations) dislike Fanny’s abstention (refusal to participate in) from the play. They think she is prudish (awkwardly self-righteous and distant) and not just shy.

However, Austen used Fanny’s stance (moral position) to make a point that readers in her day would have recognised. At that time, acting was seen as something that less respectable people (not very honourable people) would do. Often actors and actresses would live immoral lives by the standards of their day.

As a result, even while many wealthy families, including the Bertrams (and even the Austen family), occasionally put on ‘home performances’ of Shakespeare or other plays, these were always thought to be something that should be kept inside the family and not displayed to the general public. This was important because women were expected to be modest and not show themselves off (in acting, or any other kind of public show of feelings or experiences). This was seen very differently from home performances, where sisters could play a dramatic role in front of their parents and brothers without embarrassment, as Jane Austen herself did when she was a girl.

Austen would like us to understand Fanny in light of this (taking this into consideration). Fanny was not only being modest, she was behaving with proper respect towards her uncle, her family, and also the standard of feminine behaviour in her day. By contrast (on the other hand), her female cousins Maria and Julia are all too ready (far too ready) to act in the play.

📕 ‘Me!’ cried Fanny, sitting down again with a most frightened look. ‘Indeed you must excuse me. I could not act anything if you were to give me the world. No, indeed, I cannot act.’

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814, emphases mine)

Everyone at Mansfield Park (the home of the Bertram family) continues to prepare for the play. Chaos and disorder ensue (follow), fights follow; some members of the family become hurt and offended, while others become dangerously close to falling in love with someone they are not married to.

Fanny watches in shock and amazement.

Suddenly, the spell of acting is broken! Sir Bertram returns home unexpectedly (not having been expected) and angrily breaks up the acting group.

We can read this as a symbol of something bigger: Austen is preparing her readers for what will follow later on, when another ‘playing’ with moral standards will lead to a sudden disaster.

Meanwhile, Fanny continues to be useful to her aunt. She is a companion to Lady Bertram and reads to her on dull (uneventful) evenings. This pastime (hobby) suits them both since they are tranquil (peaceful, calm) and quiet persons. It pleases Fanny in particular, because she loves to study the classics and practice reading them aloud.

It is at such a quiet moment that Edmund Bertram, the cousin she loves and admires the most, walks into the room with Henry Crawford.

Henry is a young, careless, and lively man who has been making other ladies fall in love with him without ever falling in love with them. But the more he observes Fanny, the more he finds himself unaccountably (inexplicably, unable to be explained) fond of her (feeling affectionate for her).

For her part, she dislikes him very much and even fears him, because she has seen how much he enjoys making other women – such as her cousins Maria and Julia – fall in love with him. These women have been heartbroken (deeply hurt and rejected), because once he became bored of them, he was quick (ready) to abandon them. Fanny remembers this, and is wary (cautious, careful, alert to danger).

📖 SCENARIO 2: READING SHAKESPEARE IN THE MANSFIELD PARK CIRCLE

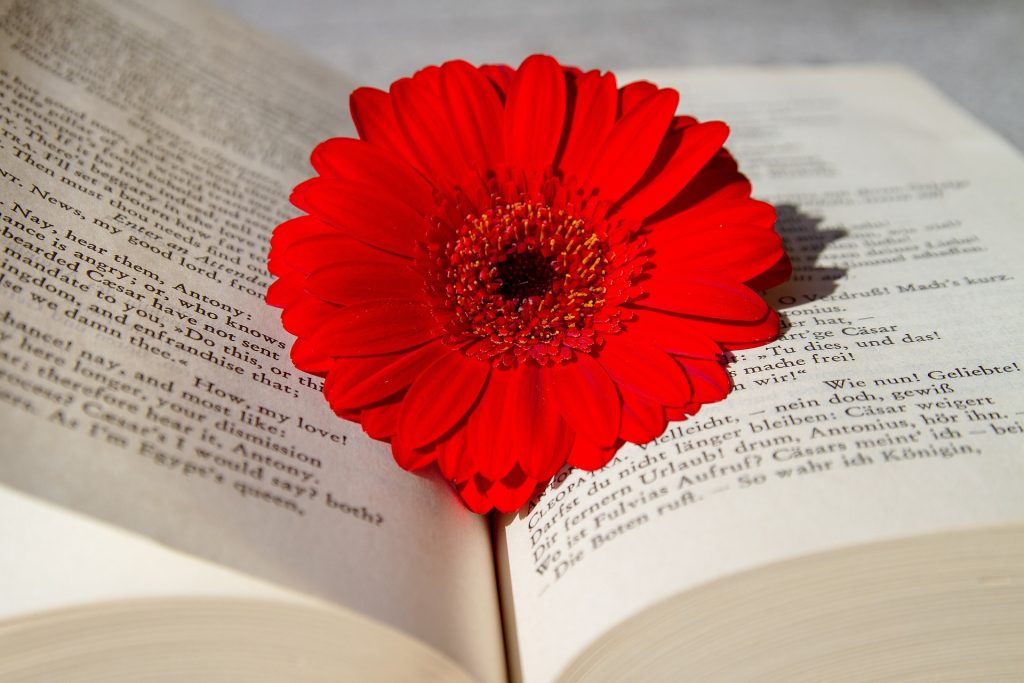

In this scene, she is with her Aunt Bertram, quietly reading from a volume (book) of Shakespeare, when Edmund Bertram and Henry Crawford walk into the room.

📕 When he [Edmund] and Crawford walked into the drawing-room, his mother and Fanny were sitting as intently and silently at work as if there were nothing else to care for. Edmund could not help noticing their apparently deep tranquillity.

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

📕 And sure enough there was a book on the table which had the air of being very recently closed: a volume of Shakespeare.

[Lady Bertram speaking] –“She often reads to me out of those books; and she was in the middle of a very fine speech of that man’s — what’s his name, Fanny? — when we heard your footsteps.”

Crawford took the volume.

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

At this point, things take an interesting turn. Fanny has been determined to withstand (resist) Henry’s advances (his attempts to win her), but while she listens to him reading aloud and impersonating (pretending to be the characters of the play) the different persons in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, she – Fanny, whom we know is usually so resolute and firm – is almost spellbound (as if caught in a spell, forgetting the situation because she is fully absorbed by what she hears).

The following sentences are written as a single paragraph in the original text. 🫴 To better comprehend and appreciate them, let’s divide them into separate lines.

As always, the changes in font (emphases) are my own.

📕 She could not abstract [remove, turn away her concentration] her mind five minutes: she was forced to listen;

his reading was capital [excellent, without parallel], and her pleasure in good reading [was] extreme.

To good reading, however, she had been long used: her uncle read well, her cousins all, Edmund very well,

but in Mr. Crawford’s reading there was a variety of excellence beyond what she had ever met with.

The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all [these characters in Shakespeare’s play] were given [performed, interpreted] in turn;

for with the happiest [luckiest] knack, the happiest power of jumping and guessing, he [Henry Crawford] could always alight [seem to arrive] at will [as if by his own choice] on the best scene, or the best speeches of each;

and whether it were [subjunctive tense] dignity, or pride, or tenderness, or remorse [deep regret for wrongdoing], or whatever were to be expressed,

he could do it with equal beauty.

It was truly dramatic.

His acting had first taught Fanny what pleasure a play might give, and his reading brought all his acting before her again [his reading reminded her again of all his acting earlier in the story];

nay [no], perhaps with greater enjoyment,

for [because] it came unexpectedly [because she wasn’t prepared for the powerful influence it would have on her],

and with no such drawback [without the same problem, downside, shortcoming, weakness] as she had been used to suffer [when] seeing him on the stage with Miss Bertram [flirting with Maria Bertram’s feelings with no intention of being serious or marrying her].

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

It is interesting that Austen would choose Shakespeare’s play Henry VIII as the one that Henry Crawford reads aloud from. Like his namesake (a person who shares the same name, usually someone who has lived long before or is famous in some way), Henry Crawford loves many different women.

He doesn’t know the changeability of his own heart: he thinks he loves Fanny, just as Henry VIII initially loved the quiet Queen Catherine of Aragon. However, later on in the story he will temporarily fall in love with a livelier woman, the now-married Maria Bertram. His is a short-lived romance exactly like that of Henry VIII with Queen Anne Boleyn, and Austen would like us to see Henry’s instability (lack of dependability, of stability in his character) in this light.

In this scene, however, Henry Crawford is still enamoured with (in love with, almost to the point of obsession) serene Fanny (tranquil, peaceful Fanny). As he finishes reading, he notices that Fanny has been admiring his reading in spite of herself (despite not wanting to).

Edmund Bertram comments that Henry Crawford must know the play very well to be able to interpret it so vividly (excitingly, with life and energy). Edmund likes Henry and hopes that he succeeds in winning Fanny.

Next comes Henry’s response. Let’s break it down once again. It will help us not only to understand the English vocabulary and expressions, but also to notice Austen’s tiny hints of her belief that Shakespeare can bring out our true character.

📕 “It will be a favourite, I believe, from this hour,” replied Crawford;

He says this to try to get Fanny’s attention – as if by reading this particular Shakespeare play in her presence, it has suddenly become his favourite!

📕 “but I do not think I have had a volume of Shakespeare in my hand before since I was fifteen.

Here we see that Henry Crawford actually hasn’t picked up any play by Shakespeare since he was fifteen! It would seem that when he was a boy at school, he depended on his teachers to tell him what to read.

📕 I once saw Henry the Eighth acted, or I have heard of it from somebody who did, I am not certain which.

This is a sly, humorous little observation on Austen’s side: we are supposed to notice that Henry Crawford is so flippant (not taking things seriously enough) that he cannot even remember if he really once watched his ‘favourite’ play being performed, or just heard somebody talking about it!

Austen has a high regard for people who can appreciate and remember good literature. You can see this in her other works as well, especially ‘Persuasion’, ‘Northanger Abbey’, and ‘Sense and Sensibility’.

In what follows, however, we read Henry’s most memorable words:

📕 But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with [a person becomes familiar with] without knowing how. It is a part of an Englishman’s constitution [what makes a person whole: body, soul, and spirit]. His thoughts and beauties are so spread abroad [so widespread] that one touches them everywhere; one is intimate [deeply familiar] with him by instinct. No man of any brain [of any intelligence] can open [open a book of Shakespeare] at a good part of one of his plays without falling into the flow of his meaning immediately [understanding his flow, his meaning, his direction immediately].”

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

Notice how Edmund continues this conversation, as Henry has done, using the impersonal word ‘one’ to mean ‘anyone’ or ‘everyone’.

📕 ‘No doubt one is familiar with Shakespeare in a degree,’ said Edmund, ‘from one’s earliest years. His celebrated [famous] passages are quoted by everybody; they are in half the books we open, and we all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions; but this is totally distinct from giving his sense as you gave it. To know him in bits and scraps is common enough; to know him pretty thoroughly is, perhaps, not uncommon; but to read him well aloud is no everyday talent.’

– Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814)

Austen expects us to pick up on (recognise, realise) poor Edmund’s blindness here: he somehow forgets that Henry has just said he hadn’t read a volume of Shakespeare in years. Instead, Edmund starts talking about ‘knowing [Shakespeare] pretty thoroughly … [and being able] to read him well aloud is no everyday talent’.

On the other hand, Fanny wakes from her spell. She can recognise Henry’s gift as a reader, but she also remembers that his talent for acting out roles – such as pretending when he is with different women that he is in love with them – does not accord with (align with) her own morals. Quietly, firmly, she sets herself strongly against falling for his charms (attractions).

…

💭 REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Do you think that Austen approved of (believed in, agreed with, thought well of) acting out Shakespeare’s plays?

- Did Austen see a difference between, on the one hand, being able to act or read Shakespeare’s plays well, and on the other hand, being able to understand them fully, with the heart as well as the mind?

- How did Shakespeare’s play Henry VIII (and Henry Crawford’s comments afterwards) help Fanny realise that Henry was a dangerous, changeable man?

…

🪶 CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

There are so many references to Shakespeare in the novel that it would be impossible to list them all here.

At this point, it is enough to say that Fanny has realised something that Austen would have wanted her readers to understand as well:’moral and literary tastes’ should align with each other. ✨ A person who has truly admired and considered the value of literature ought to be affected by it as well. It needs to have a pervading (strongly influencing, permeating) every aspect of how he or she lives.

Unfortunately for Henry Crawford, Shakespeare only affected his feelings and his imagination, but not his moral behaviour. Like a good actor, he could slip out of one role and into another without much thought or care, just as he does (later on in the novel) when he suddenly gives up trying to win Fanny and seduces Maria Rushworth (née Bertram) instead.

Contrarily, Fanny is the type of person who not only reads Shakespeare and many other classics (see Chapters 2 and 16 in the novel), but also memorises and muses over his best lines. She takes them to heart. And as a result, they assist in educating her about the moral pitfalls that any young person may encounter.

🌹

In the end, Fanny doesn’t need to act out any dramatic role to appreciate Shakespeare. For Austen, full appreciation of the famous playwright’s works – and of good literature in general – comes from taking the time to reflect thoughtfully, deeply, and sensibly on what we read.