It has been a while since we turned to Charles Dickens for educational inspiration! On the other hand, I have just finished reading the last chapters of my favourite Dickens’ book, Little Dorrit (1857), and am paying tribute to it (acknowledging it respectfully) in today’s Lesson on homophones.

You might be asking: what are homophones?

✍️ These are simply words that sound the same but are spelled differently, and sometimes even carry a different meaning from one another.

As such (notice how I use ‘as such’ – you can check out our Lesson on this little phrase here), homophones are hugely important for anyone who is studying English! I believe English might have more homophones than most other European languages (with notable exceptions such as Chinese or French).

This would be on account of English being derived from (coming from) a variety of different language origins. For this reason, many English homophones are not even related to each other (as they usually are in French, for example). 👉 Think of ‘bare’, which is of Germanic origin, compared with ‘bear’ which is from an Indo-European root of Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin.

One of the best homophone jokes in Dickens’ works can be found in Little Dorrit – and so this was the reason behind my pairing (matching) this topic with this particular novel. ✒️

After you have read the Lesson, try guessing for yourself which quotation contains his joke (British humour style)! Tip: I have just hinted at it in my last short paragraph above!

…

📝 LITTLE DORRIT: A BACKGROUND OVERVIEW

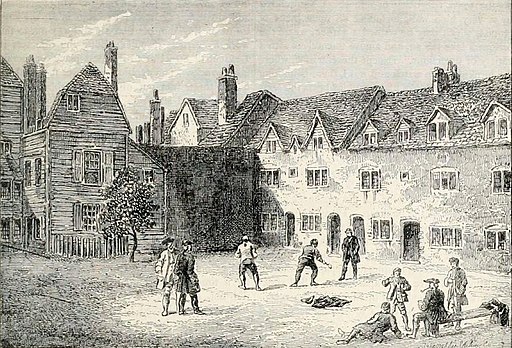

As for today’s literary text, Little Dorrit, Dickens wrote this novel to relate (tell) of the plight (fate; difficult destiny or experience) of impoverished (made poor) people who used to end up in a debtors’ prison because they could not repay their debts.

Image Credit: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

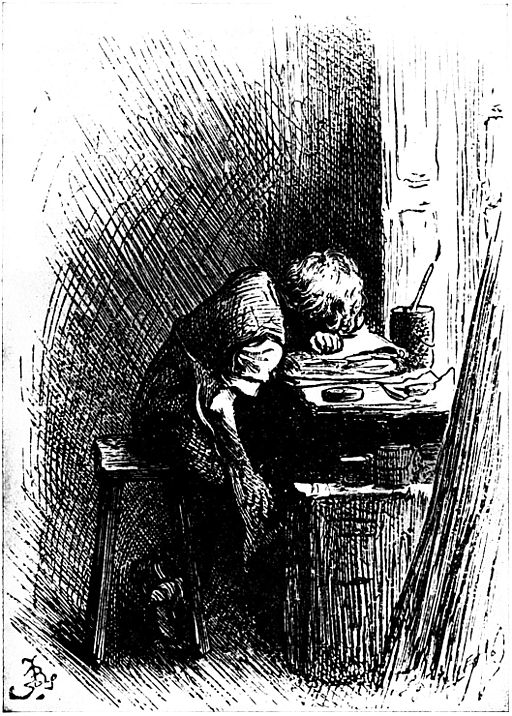

It was a very personal story for him since as a child his own father spent some years in such a prison, called the Marshalsea. As a young boy, Dickens had to leave school and start working long hours in a blacking factory to help his family make ends meet (cover the costs of living).

Image Credit: Artist Fred Barnard, died 1896., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In his novel, Little Dorrit is the name of a girl who was born in this same prison while her father was imprisoned there, and as she grows up, she works outside the prison walls as a seamstress (a person who sews and mends clothes for a living) to financially support her family. 🧵

🗝️ The story offers a strong contrast between financial imprisonment, such as the kind that the Dorrit family experience, and the moral or metaphorical imprisonment of rich people nearby who see the pain of others and yet continue to live selfishly in society.

Image Credit: W. P., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Along the way, Little Dorrit meets with a man called Arthur Clennam who has just returned from China and wants to live purposefully and generously. His plans to support a poor inventor are gradually thwarted (prevented from being accomplished) and for a time it seems as though all is lost, but the virtue of honesty and friendship carry him and his closest friends through their darkest hours.

It is a beautiful story with a social moral, and one that I love to revert to whenever I can!

We will only touch on some of its lines here – sentences that help to illustrate commonly mistaken homophone pairs – and I will offer a short context for the quotations as we go.

…

📝 FARTHER vs FURTHER

These two words, being close in meaning, are often confused.

✍️ ‘Farther’ tends to refer to actual physical distance between persons, places, or objects.

✍️ On the other hand, ‘further’ refers to metaphorical or figurative distance.

When Little [Amy] Dorrit meets Mr Clennam far from her home, she assures him that she is not afraid of being at such a distance:

📙 “I have been much farther away from it than this; but then I took the best part of it with me, and missed nothing. I felt solitary as I dropped asleep here, and, missing it a little, wandered back to it.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

By contrast, notice how in these next examples all references are to something other than physical distance – you can use ‘further’ to describe ‘notice’ (‘without taking any further notice’ meaning ‘not showing any more notice …’), or ‘further explanation’ (meaning ‘more explanations’), or ‘no further anxiety’ (meaning ‘no more additional anxiety’).

📙 ‘[Monsieur Rigaud] walked out into the side gallery on which the door opened, without taking any further notice of Signor Cavalletto.’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

Monsieur Rigaud is the villain (bad hero; main evil character) of the story, and tends to ignore anyone who doesn’t want to help him, such as the small Italian man called Cavalletto:

Some time later in the story, when the Dorrits have discovered a new fortune, they go travelling. Little Dorrit’s brother Edward has become cocky and arrogant through his having inherited new riches, and in this next sentence, when a stranger hints that he should make room for other people, Edward’s first reaction is to ‘demand further explanation’ rather than obey.

📙 ‘[Edward Dorrit] seemed about to demand further explanation …’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

This next quotation comes from the words of a lady called Mrs General. She is hired by Mr Dorrit to train his daughters – including Amy, or Little Dorrit – to become aristocratic ladies. Here she is trying to assure Mr Dorrit that if Amy follows her direction and learns manners from herself (Mrs General), then Mr Dorrit won’t have anything else left to worry about.

📙 “If Miss Amy Dorrit will direct her own attention to, and will accept of my poor assistance in, the formation of a surface, Mr. Dorrit will have no further cause of anxiety.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

✍️ But ‘further’, unlike ‘farther’, can also be used as a verb. See how it is used below to describe ‘advancing’ or ‘putting forward’ someone else’s interests or wellbeing. (Mr Dorrit is talking about ‘furthering’ the interests of a poor artist, but in reality he only wants to befriend this artist because he has aristocratic connections and Mr Dorrit wants to move in higher social circles).

📙 “Well!” said Mr Dorrit. “It would be very agreeable to me to present a gentleman so connected, with some— ha— Testimonial of my desire to further his interests, and develop the— hum— germs of his genius.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

…

📝 PRINCIPAL vs PRINCIPLE

✍️ ‘Principal’ as an adjective means ‘main’ or ‘primary’, but as a noun it refers to the main person or leader in charge of a school or business.

Charles Dickens uses it in both senses in Little Dorrit.

Try to guess which ones are adjectives and which is a noun.

📙 “The principal pleasure of your life is to remind your family of their misfortunes.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

📙 “His principal anxiety was about his wife.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

📙 ‘On this hint, Mr Plornish retired to communicate with his Principal, and presently came back with the required credentials.’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

This last line describes Mr Plornish, a poor labourer who always consults his wife whenever he needs advice. (Dickens liked to include rich and poor characters moving about in London in nearly every novel, and Mr Plornish and his family are some of the ‘honest poor’ he wrote about). Dickens jokingly describes Mrs Plornish as ‘[Mr Plornish’s] Principal’, just as if she were her husband’s leader and in charge of handling family affairs.

✍️ As for ‘principle’, this means a rule of truth that can serve as the basis for a belief or a behaviour. It can also refer to a moral code or rule, as mentioned in our next quotation:

📙 ‘In the constant effort not to be betrayed into a new phase of the besetting sin of his experience, the pursuit of selfish objects by low and small means, and to hold instead to some high principle of honour and generosity, there might have been a little merit.’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

✍️ The phrase ‘in principle’ simply means ‘in theory’ or ‘generally speaking’, especially when the speaker or writer hasn’t given many details about what that theory involves. You can see how Mr Dorrit, the speaker in the next quotation, is speaking in a general and vague way about what he wants to say (he is trying to defend his son Edward’s proud arrogance as the ‘right’ thing to have, now that they are all rich).

📙 “… which, in principle, I— ha— for all are— hum— equal on these occasions— I consider right.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

…

📝 COMPLIMENT vs COMPLEMENT

This is a tricky pair of homophones! ✍️ We will start with ‘compliment’, which as a noun is defined as ‘a polite expression of praise or admiration’. We can also use it as a verb or else just write, as Dickens does below, ‘pay [someone] a/the compliment’.

In our next quotation Dickens also makes a play on words, which for a non-native English reader might be a little confusing at first. Basically, while Mr Dorrit was still in prison, he used to hint at every person who visited him that he was open and willing to accept gifts and donations. He called these donations or monetary gifts ‘compliments’, just as if they were a tribute to a great person. (In other words, Dickens wants us to see that even before Mr Dorrit was freed from jail and became rich, he was obsessed with trying to look important). 🎁

Whenever someone did pay him a tribute, he accepted it with plenty of compliments or polite expressions of praise and gratitude in return. He then uses these monetary gifts to buy expensive things for himself, including a billiard table (these were used for playing billiards, a fashionable game), a new shining collar, bright buttons, and more. 💰

📙 ‘Whoever had paid him the compliment, he very readily accepted the compliment with his compliments, and there was an end of it. Issuing forth from the gate on these easy terms, he became a billiard-marker; and now occasionally looked in at the little skittle-ground in a green Newmarket coat (second-hand), with a shining collar and bright buttons (new), and drank the beer of the Collegians.

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

Again, we see ‘compliment’ being used in other places, such as in our next sentence where it is used as a verb (in the imperative tense – as a command).

Here the stern Mrs Clennam (mother of Arthur Clennam) answers the flattering French villain, Mr Rigaud (also known by his fake name, Blandois):

📙 “Don’t compliment me, if you please.”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

As Dickens didn’t use the word ‘complement’ in his novel, I will just provide a short definition and a sample sentence to show how it differs from ‘compliment’ as already explained:

✍️ ‘Complement’ is something that ‘contributes extra features to something else, to make it complete’. In English grammar, once we have identified the main part of the sentence, we call whatever is left the sentence its ‘complement’ because it helps to complete the whole sentence’s meaning.

Here is a sample sentence using ‘complement’:

✒️ Her pink shoes were a suitable complement to her rose-coloured outfit.

✍️ And as a verb, ‘to complement’ simply means to ‘contribute extra features to something else as to improve or emphasise their qualities’. For example:

✒️ The chocolate toppings complement the cake’s coffee flavour. [In other words, the toppings add something to the cake’s existing taste.]

…

📝 REAL vs REEL

I imagine that the word ‘real’ is fairly clear for you! ✍️ It is the opposite of ‘not true’ or ‘not factual or actual’, as can be seen here:

📙 because of some resemblance, real or imagined, to this first face that had soared out of his gloomy life into the bright glories of fancy. He

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

✍️ On the other hand, its homophone counterpart, ‘reel’, refers to

- (NOUN) A cylinder on which tape, film, wire, etc. can be wound.

- (NOUN) A lively Irish or Scottish folk dance

- (VERB) to wind something around a reel by turning it ✍️

- (VERB) to lose one’s balance and stagger or move about awkwardly and violently

In this next sentence, Dickens is describing Mr Merdle, a wealthy and highly influential banker, who is able to bribe his way through politics and effortlessly wind or draw to himself constituencies (group of voters in a specified area) as if they were just a thread on a cylinder going straight into his pocket and providing him with financial profit (see the third defined meaning listed above ✍️).

It is an interesting word to use, because it suggests the smoothness of dishonest and secretive political dealings in Mr Merdle’s world.

📙 ‘… out-of-the-way constituencies, that had reeled into Mr Merdle’s pocket.’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

…

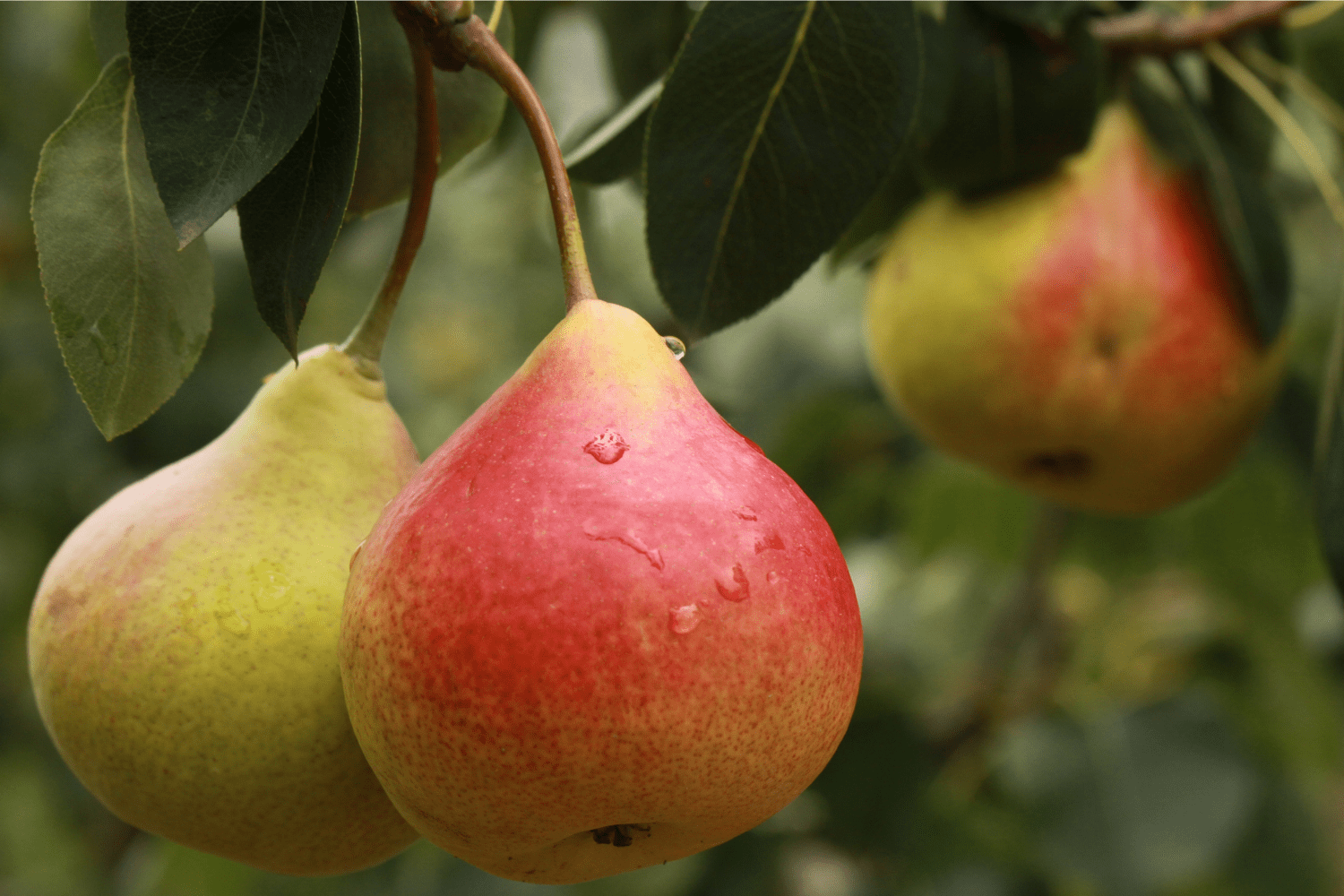

📝 PEAR vs PAIR

📙 ‘… from Eton pears to Parliamentary pairs …’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit

Have you ever eaten a pear? ✍️ These are delicious fruit with a yellowish or brownish-green colour and having a distinctive shape (as can be seen in our Lesson’s feature image). They tend to be juicy, with a mildly sweet taste.

The speaker of our next quotation, Lord Decimus, is showily talking about how he used to have pears while at school (Eton College – a prestigious boys’ school) and is now a member of the British parliament (an MP) working with another MP as a political ‘pair’ (✍️ two people working or associating together).

He makes a joke that he hasn’t been able to distinguish between the 🍐 ‘pears’ of his boyhood and the 👬 ‘pairs’ of his present political life:

📙 ‘It was a joke of a compact and portable nature, turning on the difference between Eton pears and Parliamentary pairs …’

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit

Dickens describes Lord Decimus as repeating the joke over and over, still finding it humorous (funny) long after everyone has heard it many times! He even mentions it one more time as he goes down the stairs with his friend:

📙 “And so we pass, through the various changes of life, from Eton pears to Parliamentary pairs …”

– Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (emphasis mine)

…

🍐 🍐 🍐

That brings us to the end of this week’s Lesson on homophones!

I trust it helps you to learn, even memorise, the differences between some English words that sound similar but have very different meanings and spellings (👉 if you are interested, I also wrote another Lesson on homophones some months ago, which you might like to check here).