As you may remember, every second Saturday we take the time to look at a poem from English or American literature. This week I am sharing with you a poem by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (whose poem, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’, we looked at in Lesson #187). 🖋️

As I thought about this poem and read it through several times, I wondered how best to present it in this Lesson. Should we focus on the vocabulary? Or should we read it for its rhythm?

Since it is such a thoughtful poem, I decided that for a change it would be nice just to read it through with you, highlighting anything that I think might be important but focusing mainly on understanding what the poem really means. 💭

By doing so, it seems to me that the poem will become more memorable for you than if I were just to analyse it for its grammar or poetic structure.

It will be like sharing a poem with a friend, talking simply about how it has made an impression and why! 💮

If you want to benefit even more from this Lesson, feel free to take what interpretations I have written as a reading comprehension exercise, and write your own responses to the questions below. (Try to answer each with one or two sentences at most, and if you send them to me before May 31st 2021, I will be happy to read and correct them for you.)

- What is Longfellow’s main message here?

- What part of the poem resonates (touches, connects) with me the most?

- If I had to write a poem on a similar topic, what would I like to emphasise?

‘A Psalm of Life’ is a deeply personal and powerful poem. I am sure you will find at least one line from it that stays with you after you have finished reading it. 🏵️

…

📝 ABOUT THE TITLE – ITS BACKGROUND AND INFLUENCES

Its title, ‘A Psalm of Life’, refers to the ‘psalms’. ‘Psalms’ are Biblical poems (150 in total) that speak of the emotional and spiritual journeys of the soul. They were mostly written by David, one of the first kings of ancient Israel, with a few written by Moses and other writers.

In Christian traditions, they are often read at special ceremonies, especially funerals. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow himself wrote this poem shortly after the death of his wife Mary Storer Potter, when he was still trying to make sense of her death. Around this time, he had written in his diary: ‘One thought occupies me night and day … She is dead – She is dead! All day I am weary and sad’. He spent some time talking with his friend Cornelius Conway Felton about ‘Life’s battle’ and how to ‘make the best of things’, a conversation that influences the tone of this poem.

Longfellow was also influenced by the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). If you are familiar with this great German writer, you too may recognise some of his influence on Longfellow through the lines below.

…

📝 THE POEM

(Note: You can also find the poem – without my interpretations interrupting the flow – on the Poetry Foundation’s website.)

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

In this stanza, Longfellow wants us to remember that life is more than ‘mournful numbers’, that is, statistics. He believes that when a person’s soul sleeps (by not having any special interest or energy) it can be described as ‘dead’.

What we can perceive (notice, observe with the senses) outwardly is not the whole reality – 📜 ‘things are not what they seem’.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

As you will notice throughout, this poem is full of exclamation marks (!). Why does Longfellow use them so often, especially when most poems do not generally have that many?

I think Longfellow is utilising (using) punctuation here to emphasise, visually and aurally, the urgency he is feeling as he thinks about life and death. (If you listen to narrations of this poem on YouTube, for example, you will notice that good narrators tend to stress these exclamations either by a meaningful pause (as in this one read by Tom O’ Bedlam) or else by reading them energetically (as in this one read by Tim Gracyk).

📜 ‘Dust thou art, to dust returnest’ – this is a quotation from the Bible, where God cursed the first human beings, Adam and Eve, for their disobedience. This line simply means that they will not live forever; they came from dust and will become dust after they die.

However, Longfellow assures us in his next line that this curse was never ‘spoken of the soul’ 📜 – in other words, the soul is eternal and will not die and return to dust, as they body will.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

It might seem like a contradiction, but in this stanza Longfellow is reminding us that we are all going to die in the end – our lives are like steady, slow marches that will end in the grave, just like a funeral procession. However, by using words like ‘drums’, ‘beating’, and even ‘marches’ (a ‘march’ is not simply a ‘walk’ but an ordered, disciplined, even military procession), Longfellow is reminding us that even though we know we are going to die eventually, we can live life with energy and purpose just as if we were soldiers marching with hearts that are 📜 ‘stout and brave’.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

A ‘bivouac’ is a basic camping structure without either covers or a full tent. This emphasises that we are alive for a short duration – unlike a house, which is more lasting, a bivouac is the most flimsy and unendurable kind of shelter!

‘Strife’ is another synonym for ‘battle’, ‘conflict’, ‘fight’.

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,— act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Again, here we find another reference to a Biblical text: 📜 ‘Let the dead … bury its dead’ (it comes from Luke 9:60) meant that when a person has a deep purpose in life to fulfil, they shouldn’t get distracted by trying to attend to what is no longer purposeful.

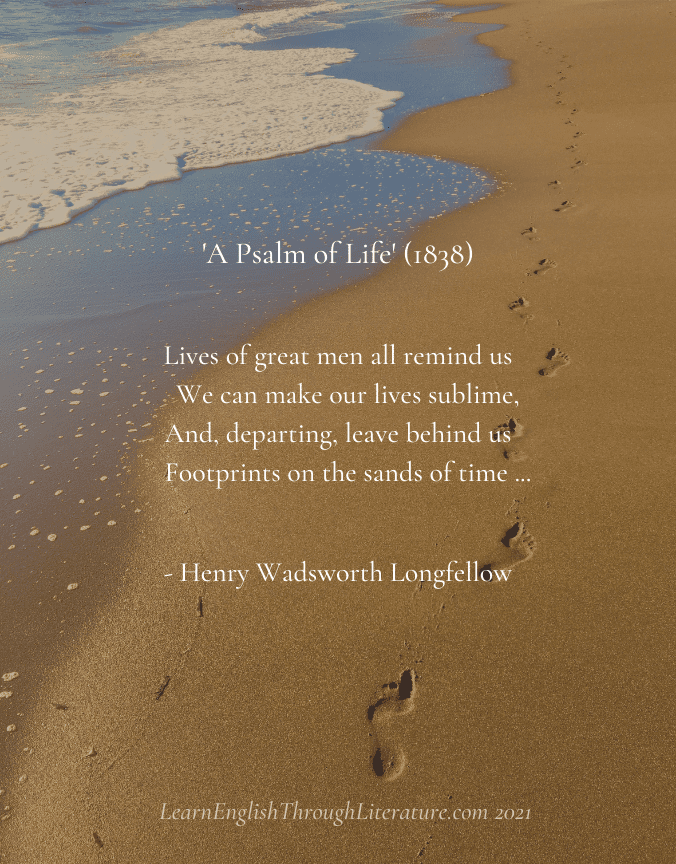

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

This is perhaps the most well-known and oft-quoted (regularly quoted) part of this poem. 📜‘Footsteps on the sands of time’ has become one of those famous lines that English speakers quote without necessarily remembering where they heard it from!

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

It might seem a bit incomprehensible (not able to be easily understood; not understandable) that Longfellow finishes this wonderful poem with the verb ‘to wait’. In our times, we are used to using this same verb in contexts where we are ‘waiting for someone or something’.

But in Longfellow’s time, a society and age in which many of Longfellow’s original audience (readers or listeners) were Christians, ‘to wait’ had the meaning of ‘learning to trust and depend’ on God. By ending with the line that we need to 📜 ‘learn to labor and to wait’, Longfellow is searching for the perfect balance between doing what we must do with all our energy (labour, work, exert ourselves) and learning to trust God completely as being greater than all human effort.

…

📝 CLOSING THOUGHTS

✍️ Longfellow has used

- punctuation,

- images of strife and sailing,

- and many imperative mood commands (e.g. ‘Let us … be up and doing’, ‘act in the living present’, ‘be a hero!’)

to make his point:

Life is short, but it can and should be filled with meaning and purpose. 🕯️

…

I hope you have enjoyed it as much as I do. In fact, I think I will try to commit it to memory (memorise it, learn it off by heart) since I appreciate it so much and hope to remember its lines whenever I might need some encouragement! ✨

What do you think? Are there any poems or quotations like it (or from it) that you would like to memorise for yourself?