Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year …

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’ (1860)

It may be that your experience with reading poetry goes back to when you were at school and studied some poetry in your own language as part of the curriculum. For some students, ‘poetry’ brings back memories of analysing lines that might be abstract or subjective, not really connected with the life of the person who is reading.

However, poetry comes in many shapes and forms, and there is a kind of poetry that almost always appeals to readers – narrative poetry. Narrative poetry basically retells a story in verse form, and today’s poem from American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is just such a poem.

‘Paul Revere’s Ride’ is part of Longfellow’s longer collection, Tales from a Wayside Inn, and tells the story of an American patriot, Paul Revere, whose 12.5 mile ride on the night of April 18th 1775 helped to spread the alarm in the neighbouring region that the British Army were approaching. In turn, other riders rode further inland, spreading the warning so that many others could arm themselves in expectation of battle. This event took place at the beginning of what become known as the American War of Independence (1775-1783).

When Longfellow began to write this poem, he did some research into the events that had happened (90 years before). However, he decided to change a few details for dramatic effect. The poem fixed the story in American imagination, and as an English language learner, it is an influential poem you will find worthwhile!

…

So in today’s Lesson we will look at parts of the poem (the full poem can be found here), observing its key features and reviewing any challenging vocabulary that it includes.

…

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

📜

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,—

One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’

…

📝 KEY VOCABULARY OR PHRASES EXPLAINED:

‘Hardly a man is now alive / Who remembers that famous day and year’: it is hard to find anyone alive now who was alive at that time and could remember that famous day and year

the British: short for ‘the British army’

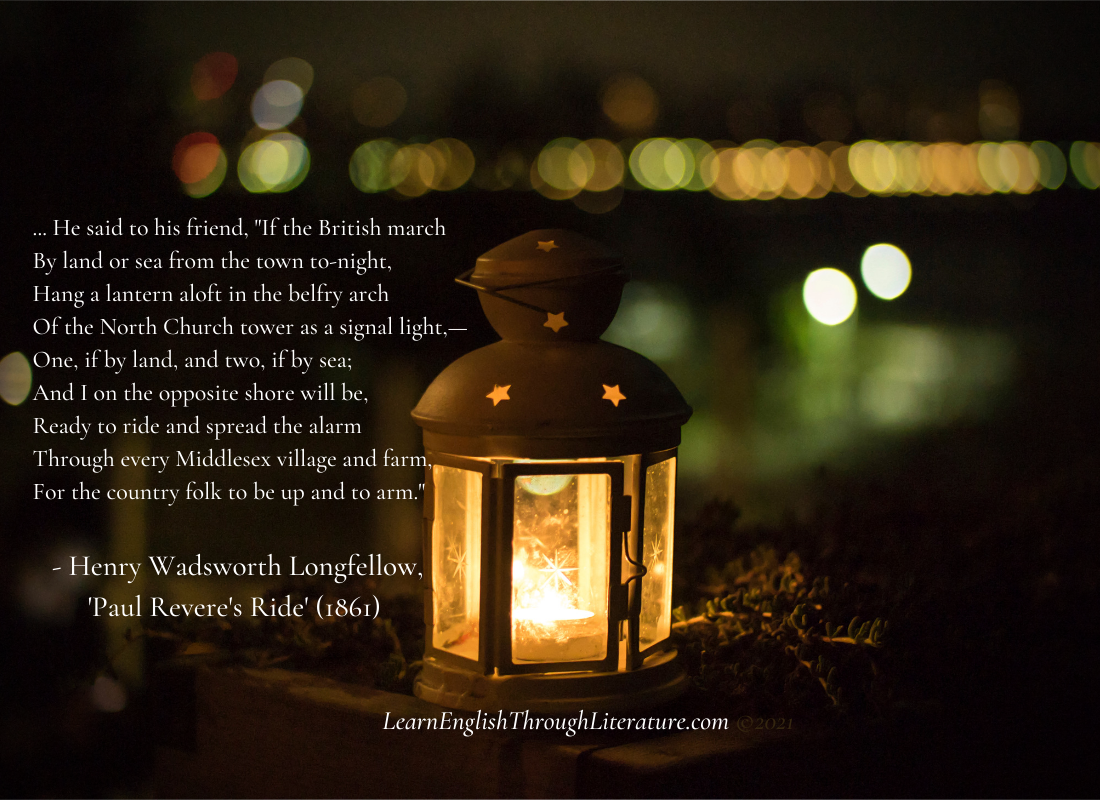

lantern: a lamp with a transparent case to protect the flame within, and having a handle with which to carry it (see the feature image above for an example of one)

aloft: above

belfry arch: the arch of a bell-tower where bells are hung from

signal: a sign that acts as a kind of warning

‘One, if by land, and two, if by sea’: ‘Hang one lantern if the British come by land, and hang two if they come by sea’

folk: people

to arm: to gather weapons to fight with

✒️ KEY OBSERVATIONS:

This passage describes an old landlord, who is the poem’s narrator (or storyteller), telling the story of Paul Revere’s ride in 1775. He describes how Paul Revere and his friend (probably a man called Robert Newman, sexton of the Old North Church) made an arrangement that would involve Newman hanging a lantern or two on the belfry arch as a sign to Revere that the British were advancing inland, either as a marching army on foot, or on boats coming up the river.

In the parts of the poem that follows, Paul Revere crosses the river to the opposite side and waits with his horse, fixing his eyes on the tall Old North Church belfry to see if he can distinguish one or two signal lights. He looks and looks, at first he sees only one, but suddenly a second one appears – the message is clear, the British army have gotten onboard some boats. So Paul Revere jumps on his horse and starts riding further west, to warn the people of the neighbouring towns and villages that the British army are approaching and that they need to be ready to fight.

We will continue with the Longfellow’s own verses from here.

…

It was twelve by the village clock,

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

📜

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.

📜

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadows brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball.

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’

…

📝 KEY VOCABULARY OR PHRASES EXPLAINED:

crowing: < crow: the loud crying sound of a cock or crow bird, especially in the early morning

damp: the moisture, condensed in the air or on a surface

galloped: < gallop: (of a horse) to ride as fast as it can, with all four feet off the ground in each stride

gilded: covered in gold

weathercock: a metal form of a cock (male hen) that used to be placed on the tops of high buildings, which would turn with the wind to show what the weather was going to be like

‘the gilded weathercock/Swim in the moonlight as he passed’: the golden weathercock seemed to swim in the moonlight as he passed

meeting-house: these were often church buildings used for religious meetings, but could also function as kinds of community centres for governmental purposes

gaze: stare after someone or something, look at something fixedly for a while

spectral: like a ghost; ghostly

glare: an uncomfortably bright light. Also a fiercely angry stare (at someone)

aghast: shocked and speechless

bleating: the weak, shaky cry made by sheep and goats

flock: a group of sheep or other similar farm animals

twitter: the high-pitched shaky singing sounds from birds

‘And felt the breath of the morning breeze’: Longfellow is describing the feeling of the morning breeze as if it were a human breath

‘over the meadows brown’: Usually we place an adjective before the noun that it qualifies; however, Longfellow has reversed this order here so that ‘brown’ rhymes with ‘town’ (a few lines above).

‘And one was safe and asleep in his bed / Who at the bridge would be first to fall …’ And someone was safe and asleep in his bed (at this time) who later in the day would be the first to die, near the bridge. It is possible that Longfellow was referring to Ensign Robert Monroe, the first officer to have been killed in the war.

pierced: having a hole made through (often for the purpose of wearing jewellery)

musket-ball: bullet

…

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled, —

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farm-yard wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

📜

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

…

📝 KEY VOCABULARY OR PHRASES EXPLAINED:

‘the British Regulars’: this was another term for the British militia

fled: < flee: run away

‘How the farmers gave them ball for ball’: how the farmers shot them back for every shot that was fired at them

fence: a railing or barrier (usually made of wood) to mark a boundary and prevent (animals or persons) from crossing into other areas

chasing: running after with the intention of catching

‘the red-coats’: a nickname for the British soldiers, who had a red uniform

lane: a narrow (usually country) road

emerge: to reappear in sight

‘to fire and load’: to shoot their guns and load more bullets into them

defiance: open and brave resistance or disobedience

echo: sound waves that follow an original sound

borne: the past of bear: carry

peril: great danger

hoof-beats: the beats or regular sounds coming from a horse’s hooves

steed: a horse for riding

…

And so you have read most of a classic poem from American literature! You have seen in this Lesson how narrative poems are used to tell a story, can include dialogue or speech of some kind, and often include descriptive language as you saw from the vocabulary lists I included here.

As I have mentioned before, if you search on YouTube for an audio version of a poem, it makes understanding the poem even easier since you can hear how words are pronounced and appreciate the rhymes that the poet intended you to notice. I will leave you with this recommended video which you can check out – a Musical Narrative of ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’. 👈