📜 ‘Consolation’

ALL are not taken; there are left behind

Living Beloveds, tender looks to bring

And make the daylight still a happy thing,

And tender voices, to make soft the wind:

But if it were not so—if I could find

No love in all this world for comforting,

Nor any path but hollowly did ring

Where ‘dust to dust’ the love from life disjoin’d;

And if, before those sepulchres unmoving

I stood alone (as some forsaken lamb

Goes bleating up the moors in weary dearth)

Crying ‘Where are ye, O my loved and loving?’—

I know a voice would sound, ‘Daughter, I AM.

Can I suffice for Heaven and not for earth?’

– ‘Consolation’, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

…

If you have been following these Lessons lately, you will know that this week we are publishing a Lesson on an English poem every day. 🕰️

In today’s short Lesson, we turn to one of my favourite women poets of all time.

🕯️ ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING (1806-1861)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a phenomenal (exceptional or remarkably good) poet and an anti-slavery campaigner in her own right, and yet she is generally remembered today as the wife of Robert Browning, himself another great poet, with whom she enjoyed a very happy marriage.

Portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning,

by the American painter, Thomas B. Read (1822-1872)

Image: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

However, her life was not without its difficulties and sorrows, among them being that for many years her father opposed her ever getting married (on the grounds that she was an invalid), so that in the end she had to elope (run away with, in order to marry) Robert Browning and leave her family for good. Another great sorrow in her life was connected with her favourite brother, Edward, who died in a sailing accident; she wrote to a friend, ‘That was a very near escape from madness, absolute hopeless madness.’

As the title of this poem suggests, it expresses the thoughts of someone who has just lost a beloved person in her life and yet, through it all, still finds consolation in the end. (I cannot trace its date, so I wouldn’t jump to the conclusion that she wrote it about her brother’s loss, although this is of course quite possible.)

✍️ One of the most remarkable things about it is its three-fold development: in the first part she describes the love of friends, then the reality of death in all its despair, and lastly the hope of a good heavenly God and life after loss.

✏️ We will focus on a line-by-line analysis and reflection on her poem, with less of an emphasis on vocabulary today so that we can focus on the general ‘sweep’ or direction of the poem.

After all, poetry is not written to be studied but instead is designed to be read, reflected on, and remembered!

…

📝 ANALYSIS AND THOUGHTS

📜‘LIVING BELOVEDS’

Elizabeth Barrett Browning reminds us through its lines of the reality of pain, sorrow, and longing by voicing the thoughts that cross our minds during different stages of our grief.

The very first phrase – ‘All are not taken’ – reads like an assertion, a reminder in face of emptiness: no, not everyone has been lost. Loss can feel overwhelming, but the poet tries to ground herself in her circle of friends and community, those who are still alive and present.

there are left behind

Living Beloveds,

She reminds herself of the simple tokens (signs) of their presence and care,

tender looks to bring

And make the daylight still a happy thing,

And tender voices, to make soft the wind:

📜 BUT IF … I STOOD ALONE …

At this point, she draws in a word of contrast: ‘But …’

But if it were not so—if I could find

No love in all this world for comforting,

Nor any path but hollowly did ring

Where ‘dust to dust’ the love from life disjoin’d;

And if, before those sepulchres unmoving

I stood alone (as some forsaken lamb

Goes bleating up the moors in weary dearth)

Crying ‘Where are ye, O my loved and loving?’—

This section essentially imagines a world without her beloved family and friends who remain: even if they were not still alive and with her, even if she were alone with ‘no love in all this world for comforting’, and on a path that rings hollow (sounds empty), there would be hope.

The next lines (from ‘Where ‘dust to dust’ the love from life disjoin’d …’ to ‘Crying ‘Where are ye, O my loved and loving?’) all go one step deeper as she tries to grasp the worst-case scenario (the worst possible situation). By writing ‘dust to dust’, the poet is repeating a line that was often used in funeral services to remind mourners (people grieving the loss of the dead person) that they will all die and turn to dust someday. The poet also talks of love being ‘disjoined’ from life: this is an uncommon word and suggests that life is like a body with many joints held together by love, but which death tries to dismantle (take a structure apart into pieces) and dislocate (move a joint away from its proper position in the body).

She introduces a third if. It is as if she wants to counteract and cancel any remaining doubts:

And if, before those sepulchres unmoving

I stood alone …

‘Sepulchres’ means tombstones, and one can imagine her here standing in a cemetery by the ‘unmoving’ graves of her loved ones, just like a ‘forsaken lamb / Goes bleating (making the crying noise that sheep do) up the moors (flat and desolate bogland) in weary (very tired and weak) dearth (a state of lacking)’.

At this point her grief turns into a lonely cry that seems to echo all around:

Crying ‘Where are ye, O my loved and loving?’—

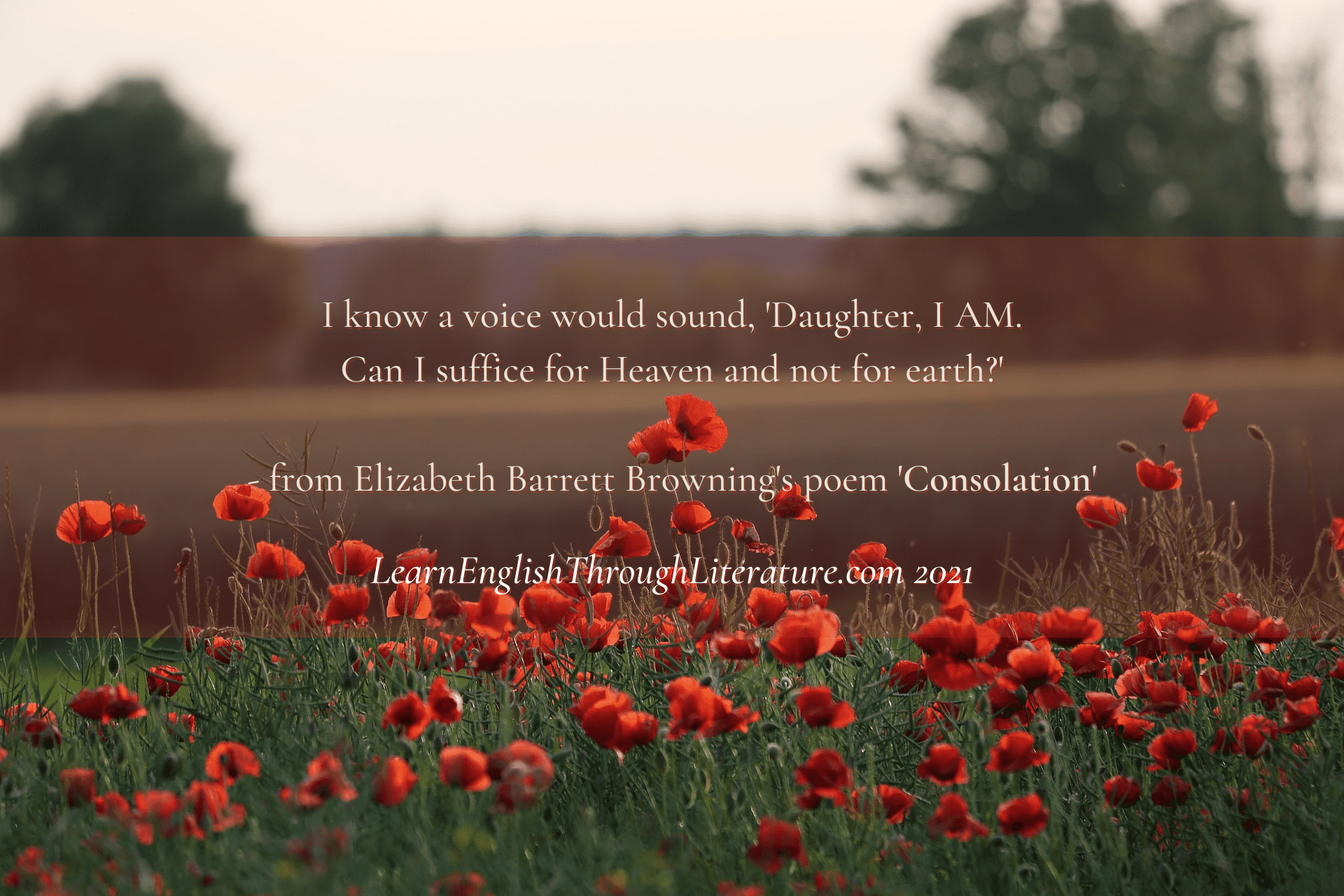

📜 I KNOW A VOICE WOULD SOUND

Despite all her anguish, she knows that she would hear an answer from somewhere, somehow: ‘a voice would sound …’

✍️ This conditional tense ‘would’ was actually more emphatic in the Victorian era when this poem was written: ‘would’ could mean, as it does here, ‘will or shall happen (in such a circumstance)’.

She is so certain of this voice answering her deepest despair that she can even imagine the words it would utter (say):

‘Daughter, I AM. …’

This capitalised phrase ‘I AM’ refers to the Biblical description of the God of the Jewish people (and later Christians), who reveals Himself to the prophet Moses as ‘I AM Who I AM’ – an enforcement of His eternal and unchangeable nature as God.

God now answers her, and the poet finds His words so amazingly comforting that she finishes with His own rhetorical question (a question that does not demand an answer because it is already self-evident):

‘Can I suffice for Heaven and not for earth?’

This sentence simply means, ‘If I can be sufficient (enough) for those in Heaven, am I not also enough for you on earth?’ The verb ‘to suffice’ means ‘be enough or adequate; to meet the needs of [someone or something]’.

In light of this closing revelation and response, the poet is silenced. Her wandering wonderings in pain and grief are hushed when she remembers that she is not completely alone and God can meet her needs even in this terribly difficult place. That is her idea of the essence of consolation – the deep comfort received by someone after a great loss, which helps them to regain their strength and live.

…

While this poem is about a serious and moving subject, I trust it has been helpful for you to read and reflect on the process of sadness and hope because, after all, it is a part of human existence everywhere. I hope you will never experience such despairing sadness, and yet it is good to know that people like Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who went through such pain before us, found a way to share their hope and consolation through eternal words.